Cyberpunk: Stuck in a weird funk?

This piece was originally published in the now-defunct Mantle Magazine on July 25, 2019.

Say cyberpunk, and we picture a sprawling cityscape full of neon lights and gigantic, holographic billboards.

“Cyberpunk is now,” goes the popular adage. Just one look at the long list of recent works in the cyberpunk genre is enough proof.

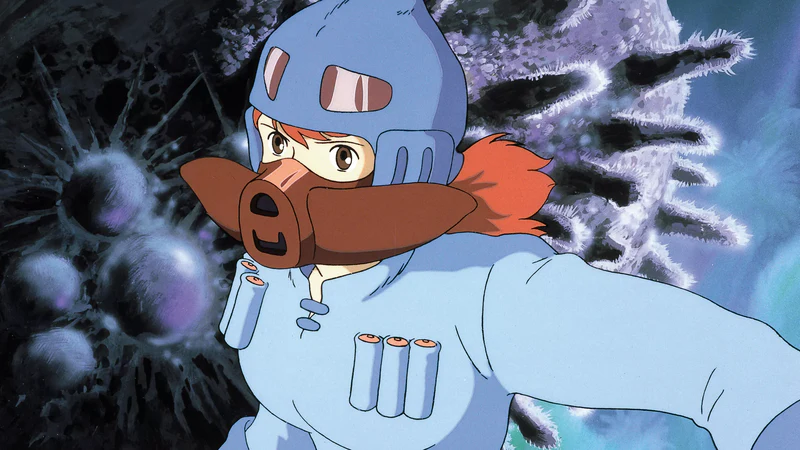

We had Blade Runner 2049 and Ghost in the Shell in 2017, Ready Player One and Altered Carbon in 2018, and Alita: Battle Angel in 2019. Plus there’s still more coming: Netflix’s Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045, Taika Waititi’s live-action film adaptation of Akira, and even CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077 (which features Keanu Reeves, who has been this generation’s ubiquitous cyberpunk protagonist ever since Johnny Mnemonic).

When someone says cyberpunk, we automatically picture a sprawling cityscape full of neon lights and gigantic, holographic billboards. We imagine the protagonists (the eponymous punks of the genre) navigating the underbelly of that city, and eventually sticking it to the mega corporations that benefit from their advanced technology while trampling ordinary citizens underfoot—all the while wrestling with their own identity and humanity. (Like the late Rutger Hauer in Blade Runner.)

But if cyberpunk is now, why has the recent revival of the genre fallen flat?

The unchanging components of cyberpunk

Cyberpunk has been around for a long time in all forms of media: from the 1960s novels written by Philip K. Dick, to films, TV series, and video games.

My first taste of cyberpunk came in 1999, when I watched films like The Matrix and Bicentennial Man, followed by The Animatrix, A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, and a very belated viewing of the original Ghost in the Shell film in the early 2000s. That was the last time we saw a surge in cyberpunk media until it started making a bigger comeback in the late 2010s.

Cyberpunk visuals have definitely seen an upgrade thanks to advancements in computer-generated imagery and animation. But beyond the aesthetics, have cyberpunk’s other elements improved with time?

Looking at some of the more recent cyberpunk films, the answer is: not really.

The cyberpunk of recent years has mostly been about homages to films and series that have come before, as if the genre were just being swept along by the recent waves of ’80s and ’90s nostalgia.

Nostalgia and nods to past successes aren’t all bad. I admit to geeking out over certain cameos in Ready Player One, and nodding in approval over scenes from the live-action Ghost in the Shell that perfectly recreate iconic scenes from the original films and TV series.

But for this genre, this obsession with the past has proven to be a problem. If cyberpunk keeps getting stuck in the past, how can it possibly tell us stories about the future?

The future of cyberpunk

Cyberpunk of the ’80s and ’90s warned us about how 2000s and 2010s could look like, and we seem to have ignored most of those warnings.

The internet keeps us connected to thousands of people around the world. Mobile and smart devices are everywhere. Grinders are hacking their own bodies. Big corporations have easy access to so much of our personal information. Virtual reality is realer than ever. Artificial intelligence keeps getting smarter. Governments are implementing social credit systems to control citizens’ behavior. Advertisements (though not as large or flashy as the ones in cyberpunk cities) can be found everywhere we go, physically and digitally.

Cyberpunk is now. Cyberpunk is here. So where else can it go?

There have been a few fresher takes on the genre, but they may not even seem like cyberpunk at first glance.

The most popular example is Mr. Robot, which essentially retains the tropes of the independent hackers taking down large organizations and swaps out the futuristic neon cities for present-day New York. Showrunner and creator Sam Esmail says that he wanted to bring cyberpunk to TV, and he does exactly that without relying on the stereotypical cyberpunk aesthetic.

Yet another popular example is Black Mirror, which, while not purely cyberpunk, has episodes that contain cyberpunk elements and themes that go beyond pure aesthetics.

What makes it both more compelling (and chilling) than many other cyberpunk works of recent years is how close to the present they set their stories. Charlie Brooker, the creator of Black Mirror, says that all of the series’ episodes are different, but they’re “all about the way we live now—and the way we might be living in 10 minutes’ time if we’re clumsy.”

This isn’t to say that cyberpunk has to give up its core elements to remain relevant today. If that were the case, then it would just be no different from everything else categorized under near-future sci-fi. But in order to still be considered punk, it has to keep up with how cyber our reality has become, and show us what new systems need to be rebelled against in order to retain our humanity.

This piece was originally published in the now-defunct Mantle Magazine on July 25, 2019.

El Santos is a marketing & advertising professional by day and gamer/bookworm/tarot reader by night. She’s prone to sudden fits of fangirling over her varied interests: video games, fiction, art, folkore, anime, and tarot. She currently lives with her husband and 2 rescue cats.